Chapter Four

Providing uninterrupted access to classes, labs and research opportunities fell to Michael Dennin, dean of UCI’s Division of Undergraduate Education and vice provost for teaching and learning, and Gillian Hayes, dean of the Graduate Division and vice provost for graduate education. The needs of these two student populations and the faculty that serve them varied widely.

Redefining undergraduate teaching and learning

Dennin’s early meetings in February and March involved an educational continuity work group, the undergraduate council of associate deans and academic advisers, and Academic Senate leadership.

“There were about two weeks in which the parameters we were working under changed every 24 hours as new information about the virus emerged,” Dennin said. “Our initial hopes were that we could finish the winter quarter in person and really plan for mostly remote instruction in the spring, with some in-person labs and studio and art courses.”

Anticipating the possibility of having to administer winter finals remotely, faculty had been testing proctoring software. Still, the final decision to do so came with just days to prepare. Undergraduate chemistry provided a good test case; all exams were held as a single final on a Sunday.

“We had the opportunity to try out everything in a single setting with faculty who had already been coordinating their exams,” Dennin said. “When that went well, it gave us confidence going into the rest of the week.”

In week 10 of the winter quarter, it became clear that spring classes would go fully online. Spring break offered a chance to record as many lectures as possible for the start of the new quarter on March 30. Faculty mobilized their resources – those more experienced in remote learning helped out those with less experience – which relieved Dennin’s group in the Office of the Vice Provost for Teaching and Learning from the sole responsibility of supporting more than 1,000 instructors.

Tom Andriola, vice chancellor for information, technology and data, said that administration of quizzes, tests and assignments through technology spurred 5,000 percent growth in the use of online platforms.

While faculty were busy recording lectures, the OVPTL assessed student technology needs. According to Dennin, ensuring that students had reliable internet connections was the biggest issue. To enable all of them to access the necessary learning materials, the OVPTL partnered with the Office of Information Technology to distribute free loaner laptops and hot spots to those in need.

To help students plan ahead, Dennin announced that summer classes, 30 percent of which were already online, would go 100 percent online as well.

“So within about 10 days, we made the decisions to do finals, spring and summer remotely,” he said.

“So within about 10 days, we made the decisions to do finals, spring and summer remotely.”

Dennin credited the successful move to online learning to teamwork and faculty agility. While acknowledging that the Academic Senate (which is responsible, along with the administration, for determining academic policy) is typically a meticulously deliberative group, he noted that it moved quickly on pass/no pass grade options, remote finals and online learning.

“There was recognition from the senate that this was a matter of health and safety,” Dennin said. “There are times you just have to say, ‘It’s a pandemic!’ I give great credit to the senate for its support and flexibility.”

The Division of Teaching Excellence and Innovation and Division of Undergraduate Education, under Dennin’s leadership, reached out to faculty and students who may have been struggling throughout the spring quarter. Targeted emails directed them to web resources for online learning and teaching strategies. Surveys done in collaboration with Student Affairs helped identify any academic anxieties. Academic counselors remained available. A webinar for faculty at midquarter was designed to answer questions about how to improve the next five weeks of remote instruction.

Ian Anzlowar:

Missing the campus community

Ian Anzlowar figured that if he had to shelter in place, Santa Barbara was a good place to do it. The third-year student in UCI’s literary journalism program gave up his apartment in Garden Grove and moved back to his home base to the north when remote instruction was implemented for spring 2020 because of COVID-19.

But as nice as Santa Barbara is, Anzlowar said he missed UCI.

“It was the first place where I felt like part of a campus community,” he said. “I went to San Francisco State right out of high school, and I was too young and not ready for it. Then I went to Santa Barbara City College, where you go to classes and then go home. UCI was by far the most inclusive and enjoyable.”

Anzlowar, 29, regretted no longer writing for the New University student newspaper. And while it might seem as if writing projects for his finals could be completed anywhere, coronavirus-related business closures made it difficult to track down and interview the sources he needed.

Normally, Anzlowar would have popped in to share his concerns with counselors, including Patricia Pierson, associate director of the Department of English’s literary journalism program.

“I’ve been reliant on her to explain things and help me stay on track to graduate,” he said. “We try to stay in touch via Zoom, but it’s not the same, and I’m constantly stressed that I’m going to forget some important deadline.”

Anzlowar acknowledged that his UCI college life would probably never be quite the same.

“I’d really like to get back to some semblance of normality,” he said. “I know we won’t return to the old normal soon, if ever. But I’d like some kind of in-person or on-campus experience. I very much miss interacting with people in the campus community.”

“With faculty frustrations, it’s not that they can’t do it,” said Andriola, who was instrumental in setting up many of the remote learning platforms faculty used in the spring. “It’s just that they don’t get the same type of student feedback they’re used to getting in a classroom. So much of what they do is working their way through the lectures with content and interaction that allows them to be great teachers, and they really have lost that.”

However, Dennin said, the pandemic afforded opportunities for growth.

For faculty, it spurred a reassessment of course curricula. The first recorded lectures remained fairly close to the in-person experience. Then, as the comfort level with the technology rose, instructors began tweaking their delivery to make the best use of online platforms. Dennin observed that as faculty members adjusted to remote teaching, they could take time to identify the core learning objectives and outcomes of their classes and let go of the “nice-to-have” features that didn’t fit in a pandemic setting.

“If we’re not self-reflective at this moment and realize that all of our courses have room to improve, then I think it’s a wasted opportunity,” he said. “When we reflect on the different things that online and in-person courses can and cannot do, we come out of this with better-designed courses.”

For students, Dennin recognized that spring classes might have seemed rough around the edges. However, he argued, the pandemic “has highlighted an element most of them realize by the end of their educational career: that their learning depends on them, and the role of the university is to make them independent thinkers. Students were still supported by faculty and teaching assistants, but in a different way.”

The graduate student challenge

Those pursuing advanced degrees – who were busy learning, conducting research, and serving as TAs and readers – faced the challenges of both students and instructors, Hayes said.

Closed labs and canceled fieldwork disrupted research and delayed timetables for finishing experiments and dissertations.

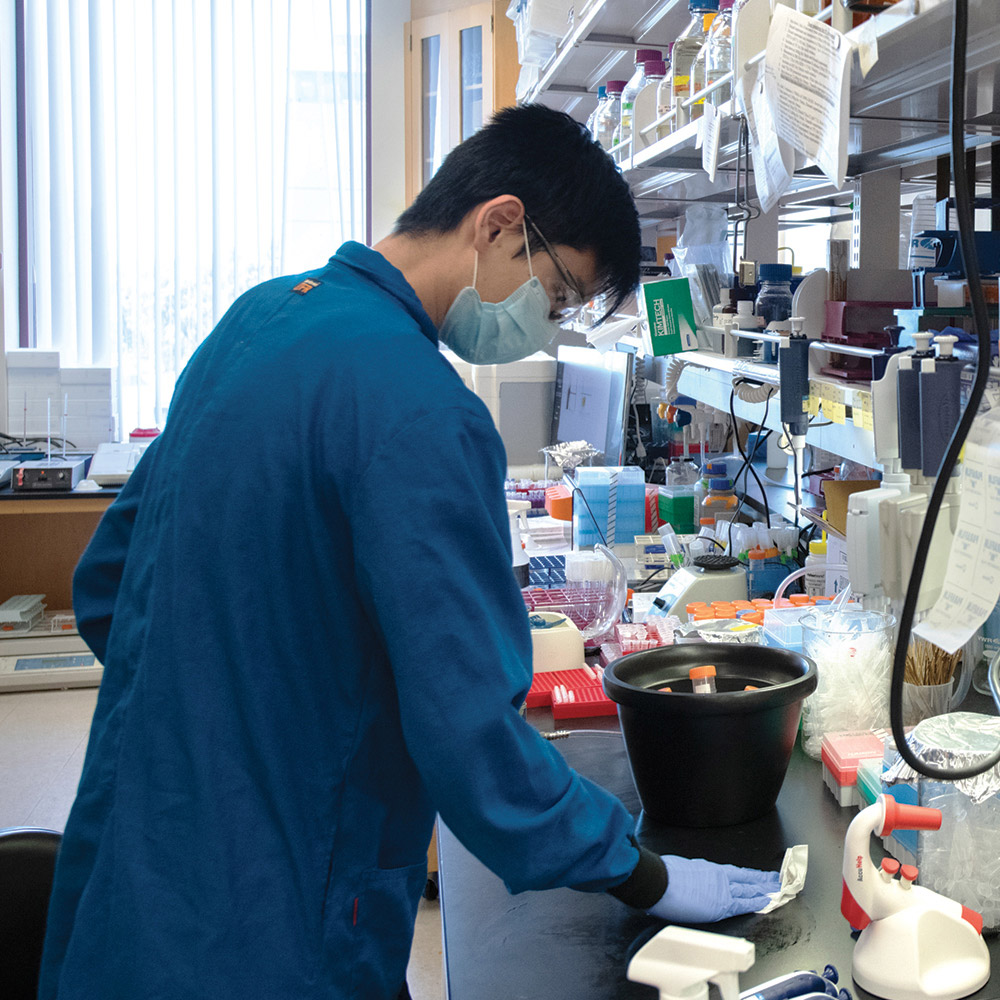

“The university pulled back a lot of students who were doing fieldwork in other countries,” Hayes said. “If they were doing fieldwork here, they often had to pull back as well. And, of course, if they were in a wet lab or needed access to an MRI machine or other physical resources, their research was put on hold – unless it was deemed essential.”

“The university pulled back a lot of students who were doing fieldwork in other countries. If they were doing fieldwork here, they often had to pull back as well. And, of course, if they were in a wet lab or needed access to an MRI machine or other physical resources, their research was put on hold – unless it was deemed essential.”

Most students could conduct data analysis and write papers, she said, but what often became problematic was the ability to collect additional empirical data, access archives or perform experiments.

On the other end of the spectrum, students doing essential antiviral research found that their efforts had suddenly become more vital. They faced extra-long workdays, while many also needed to care for elderly parents or children out of school.

Graduate students, like faculty, adapted to the new context. Not only did they have to begin holding online discussion groups with undergraduates with little time to prepare, but some had to provide tech support for faculty members as well. The university responded by hiring more TA resources, adding hours for students who were open to working more, and creating new ways to bolster the teaching mission.

Christine Mugnolo:

From the classroom to the garage

Once upon a time, Christine Mugnolo’s garage was where she parked her car. But then a pandemic hit, and the graduate student writing her art history/visual studies thesis on 19th- and 20th-century comic-strip depictions of the adolescent body was asked to conduct research from her Santa Clarita home.

So now, Mugnolo’s garage is where she retreats to at night after her three children – Violet, 7; Saoirse, 3; and James, 10 months – are in bed. There, she shakes off fatigue and tries to work until 10 p.m. Her partner has his own company, works from home and always helps manage the household. But with energetic kids around all day and needing assistance with remote learning, it’s not the ideal environment for completing a 200-page doctoral thesis.

“Things are so unpredictable,” Mugnolo said. “The week I really tried to plan, my husband threw his back out and couldn’t lift our little one. And then other days, I might get an unexpected hour to write.”

She had hoped – after eight years – to finish her thesis in spring 2020. Mugnolo started graduate school at UCI in 2012, learning at orientation that she was pregnant with her first child. Juggling a full-time job as an associate professor of studio art at Antelope Valley College, a young family and grad school meant she had to take her time.

“But I was making steady progress,” Mugnolo said. “Pre-pandemic, my oldest would get up and go to school and had activities most of the day until 4 p.m. And the little ones were in preschool two days a week. I took a one-year sabbatical from my job so I could write from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. and then later in the evenings.”

Once schools closed, both parents became teachers.

“You can’t just throw an assignment at a second-grader and then go do something else,” Mugnolo said. “My 3-year-old has trouble following her dance class on Zoom. I was trying to wean James. It was kind of chaotic.”

The UCI community was understanding, she said. The professor for whom she was a teaching assistant minimized her work. (One unexpected bonus of the quarantine was that Mugnolo no longer needed to commute from north of Los Angeles to Irvine for her T.A. duties.) Gillian Hayes, vice provost for graduate education and dean of the Graduate Division, had met with her and checked in on her periodically. Mugnolo caught bits of a few educational webinars offered by the Graduate Division.

“That’s all been very helpful,” she said.

Still on sabbatical from her job and with her older daughter on summer recess from school, Mugnolo fully expects to finish her thesis before her own kids hit adolescence – maybe even by summer 2020.

Two academic counselors on staff in the Graduate Division continued their one-on-one appointments with students and expanded access to various support groups and wellness workshops. Help also came from the Diverse Educational Community and Doctoral Experience program, made up of 80 students and faculty mentors in every graduate field of study. Program chairs and associate deans were ready to lend a hand too. Hayes set up daily office hours to offer counsel.

“We have more than 6,500 grad students,” she said, “and not all of them were in crisis. It was hectic and hard, but they were dealing. It was the ones in crisis we had to find. Uncertainty is the killer, and I spent a lot of my time telling everyone what we knew and what we didn’t know about the future to reduce the uncertainty.”

To facilitate the switch to remote classes for TAs, the campus authorized an additional $750,000 for digital pedagogy specialists who could help translate interactive, hands-on activities to the online environment. Some departments used TAs as floaters who could pitch in wherever needed. The extra jobs provided income for students whose funding was running out while their research was delayed. Similar TA support is expected in the summer and fall quarters.

For graduate students who have lost out on teaching income over the summer, Hayes created a fellowship program to help them out. Some 40 were trained to be COVID-19 contract tracers in Orange County, and another 300 participated in remote teaching assistant training program to improve their TA skills for the fall. Hayes thinks UCI may be among the few universities U.S. doing something creatively like this to keep graduate students employed and engaged during the summer.

“It’s been amazing,” Hayes said, “to see the community of graduate students willing to step up and make things work.”