Chapter Two

Almost one-third of UCI’s nearly $3 billion in annual expenditures goes toward education and services for the campus’s more than 30,000 undergraduates. Student Affairs’ diverse responsibilities include housing, food, health and counseling, and clubs and organizations.

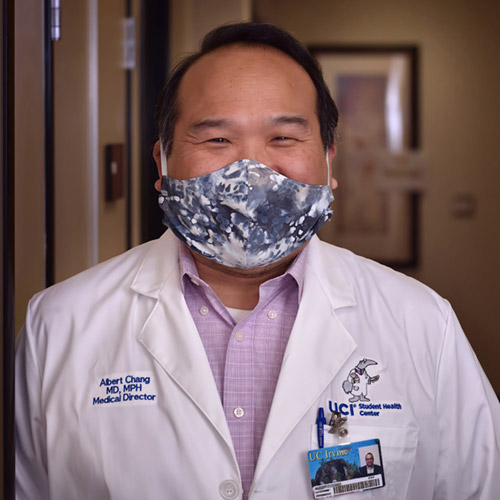

Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Willie Banks Jr. had been on the job for less than eight months when COVID-19 hit. As early as January, he and Marcelle Hayashida, associate vice chancellor for wellness, health and counseling services, along with Dr. Albert Chang, medical director of the Student Health Center, were partnering with UCI’s Office of Strategic Communications & Public Affairs to encourage students to “spread the word, not the virus.”

By Jan. 25, Bernadette Boden-Albala, director of the Program in Public Health and founding dean of the proposed School of Population Health, had deployed a student team to administer a survey assessing classmates’ level of concern and information sources. Custom T-shirts identified the students as health ambassadors, and they worked with Strategic Communications to produce videos and posters on how to properly use the portable hand-washing stations distributed around the campus.

Messaging early and often helped alleviate worries that might have led to requests for on-demand COVID-19 testing, which was highly limited at that time, Chang said. (One silver lining was that as students asked about a coronavirus vaccine, many also requested and received flu shots.)

UCI’s International Center kept in touch with the 100 or so students from Wuhan, China, where the virus was first detected. They were concerned not only about themselves, but about family members back home. Q&A sessions and workshops were conducted with them as often as needed. “I used science as a basis for the messaging to students as much as possible,” Chang said. “I stuck to what the Centers for Disease Control and the World Health Organization were saying and not what was in the media and on social media – because we didn’t want to make a statement and then have to backtrack, which would have looked like we were unsure or that we put students’ lives at risk.”

“I used science as a basis for the messaging to students as much as possible. I stuck to what the Centers for Disease Control and the World Health Organization were saying and not what was in the media and on social media – because we didn’t want to make a statement and then have to backtrack, which would have looked like we were unsure or that we put students’ lives at risk.”

March 21 saw the first announcement of a case on campus. As potential infections were identified through the Student Health Center, Chang and his staff communicated with the Orange County Health Care Agency and told housing units to have students quarantine or isolate as appropriate. With transparency as his guiding policy, Chang updated the campus on all cases as they occurred, although he did not provide enough information to breach confidentiality.

“Knock on wood,” Chang said. “With the support from campus leadership and strong, smart, healthy behaviors from our students and staff, we’ve kept pretty good control.”

The entire enterprise benefited from collaboration with Boden-Albala, who has extensive knowledge about pandemics. She recalled one particular conversation that evolved quickly from how to get students to practice physical distancing to how to send them home. At first, the discussion centered on the number of students who could safely gather in a classroom. “And I just remember saying, ‘Wait a minute. It’s not about the size of the group. It’s about the space,’” Boden-Albala said. “And the conversation turned to saliva and, literally, how far fluids can go out from the body and then to spring break and students traveling to transportation hubs and how are we going to get them back safely.”

“And I just remember saying, ‘Wait a minute. It’s not about the size of the group. It’s about the space.’ And the conversation turned to saliva and, literally, how far fluids can go out from the body and then to spring break and students traveling to transportation hubs and how are we going to get them back safely.”

“Within five days, we went from trying to work with this 6-foot barrier to ‘We’re going remote.’”

Once students and staff were sent home, Hayashida’s focus became establishing viable online mental health and support services for students experiencing isolation, financial stress, academic anxiety, sexual harassment or assault. Those services went 100 percent virtual in a matter of days. “The Counseling Center was as busy as it was before,” Hayashida said. “There was no decrease in students’ interest in maintaining sessions with their therapists. We’re posting information on social media, and there’s been a dramatic increase in engagement. Students are reacting, sharing and commenting.”

Altering dining procedures for students began with a March 6 decision to eliminate self-serve meals and encourage more grab-and-go options. Some food court vendors increased their use of robotic delivery. Students could order from Panda Express, for example, and meet a robot at a specified location for pickup.

But the realities of COVID-19 really hit home for Student Affairs when Banks canceled a large conference on the eve of the March 10 event. The gathering of 300 campus affiliates had been billed as a professional development opportunity. In the wake of calls for social distancing, Banks said, “I’m going to have to shut this down.”

“I think that was a big moment for all of us in Student Affairs,” said Rameen Talesh, dean of students and assistant vice chancellor for student life and leadership. “If we couldn’t even do our own conference with our own people in rooms that we know…. It really gave this situation elevated status.”

The student housing question

More complicated were the issues around student housing.

“Initially,” Banks said, “we were planning to move people out of certain areas of housing because we were trying to create isolation units for students who became ill.”

That quickly grew into conversations about sending everybody home, said Edgar Dormitorio, assistant vice chancellor and chief of staff for student affairs.

“We realized that once we isolated, we would really have to determine what it would take to get everybody off campus because the public perception would be that there’s a safety hazard and nobody should be here,” he said.

“We realized that once we isolated, we would really have to determine what it would take to get everybody off campus because the public perception would be that there’s a safety hazard and nobody should be here.”

The Student Affairs leadership team was preparing for a meeting on the isolation plan when they got the word: “Everybody has to go.”

Notice went out on March 10: “Students living on campus are strongly encouraged to return to their off-campus residences and, if possible, to stay at home during the spring quarter.”

After a less-than-satisfactory response, a sterner message was posted March 18: “If you are able to return safely to your permanent residence, you must do so.”

“We were first [in California] on that,” Dormitorio recalled. “And we were willing to take the criticism because we knew it was the right thing to do.”

“All of these decisions were driven by Chancellor Gillman and information he was sharing with his cabinet,” Banks added. “He was really consistent about understanding the importance of flattening the curve and social distancing and how, on our campus with so many people, it was imperative that we get people home.”

The mandated student exodus raised financial questions. Would students be held to their housing contracts?

“Happily, we had support from campus that students would not be held responsible for their housing contracts,” said Tim Trevan, executive director of student housing. UCI also bought out the leases of students living in the American Campus Communities apartments (on the university’s east side), a joint venture with a private builder.

Would financial aid intended to help with room and board costs have to be repaid? At first it seemed so, but on March 18, the U.S. Department of Education announced that student aid packages would not need to be adjusted. The federal CARES Act signed into law on March 27 also provided broad relief for students.

UCI Athletics:

When the games ended

In normal times, 300 Anteater athletes convening in the Bren Events Center would be a celebration of excellence punctuated by loud exclamations of “Zot on!” But when Paula Smith, director of athletics and senior woman administrator, gathered the students and 100 coaches and staff members for a meeting on March 11, it was a subdued crowd. These were not normal times. In light of the coronavirus pandemic, she was announcing the cancellation of the Big West Conference basketball tournament.

With highly rated men’s and women’s teams set to take the Big West by storm and contend for invitations to the NCAA’s Big Dance, the news hit like a missed go-ahead shot at the final buzzer. By the next day, athletes had learned that all spring sports would be called off. But despite what Smith called the “overt devastation” of seniors losing their basketball playoff chances and men’s and women’s spring teams losing an entire season of eligibility, students and staff appreciated that the administration had taken swift and decisive action to safeguard their health.

Then came crisis communications with ticket holders and donors about canceled events. Once past that phase, Smith went into engagement mode, making intercollegiate athletics relevant and top-of-mind among supporters. The department launched website and social media campaigns with updated stories about seniors. Coaches held lunchtime Zoom socials with backers, answering questions about future prospects.

Recruiting also went remote during an NCAA-mandated period in which coaches were not allowed to travel. Social media and Zoom campaigns highlighting UCI’s campus and athletic programs helped make the case to potential Anteaters, many of whom had already been identified by coaches.

The pandemic punched a hole in the athletic department’s budget too. The NCAA announced in March that it would slash distribution to Division I schools by $375 million. UCI also funds its programs by contracting with organizations such as the International Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Federation, which holds its Pan Jiu-Jitsu Championship every year in the Bren Events Center. But those activities and the revenue they generate were canceled this year. Ticket sales dropped to zero, and the summer youth sports camps normally held on campus were scrapped. Corporate sponsors’ ability to meet their financial commitments might also have been compromised.

As of June, Smith and her staff were working to forecast what the total loss might be and budgeting for higher fall expenditures on such things as testing and increased cleaning, while calculating what they saved by canceling the spring season. She expected to close the fiscal year in the black.

Meanwhile, seniors who had lost their last chance to compete had to decide if they wanted to take advantage of the NCAA’s decision to grant them an extra year of eligibility.

“That comes with its own set of challenges,” Smith said. “We have a high-caliber institution and academic program, and students are expected to make progress toward a degree and move on in four years. We don’t have second baccalaureate degree opportunities, so these seniors had to determine whether they could extend academic classwork or pursue a minor or master’s degree. Some were prepared to start their professional lives. Out of about 30 seniors, only 17 indicated they were interested in another year of eligibility.”

Throughout the disappointment of a thwarted spring season – during which, Smith said, she wanted to give hugs but could only do virtual high-fives and elbow bumps – she’s had faith that the Anteater family would come out stronger on the other side of the pandemic.

“Our student-athletes, coaches and staff thrive in the face of adversity,” Smith said, “and they are the most resilient group of people I have ever had the pleasure of working alongside.”

All but about 400 first- and second-year undergraduates had returned home by April. Most of those who remained were international students. A moving company helped consolidate them in Middle Earth housing. Graduate students who permanently reside at UCI also stayed, filling about 90 percent of their dedicated housing. The total on-campus student population numbered about 3,500 during the spring quarter.

Attention turned to the long-term housing implications of COVID-19. At the urging of its board of regents, the University of California had been working to ensure on-campus housing for all first- and second-year undergraduates. At UCI, that access had been achieved by building new residential towers in the Mesa Court and Middle Earth communities where as many as four students can share a room and 11 can share a bathroom. But such density is a thing of the past.

Trevan’s safe-living plan calls for changes in technology and facilities strategies to allow no more than two roommates to a space – a loss of about 1,100 beds and a financial hit of about $11 million in housing fees. Alternatively, a single-bed-per-space scheme would eliminate 3,500 beds and cost $39 million in lost fees.

“With the two-bed plan,” Trevan said, “we will barely be able to house the freshman class. We will have to figure out how to allocate available beds.”

Reducing chances for students to congregate is another painful game changer for housing staff members, who normally promote relationship building, he said, adding: “But the exciting part is that it gives us impetus to create virtual opportunities for engagement.”

Creating non-traditional commencement ceremonies

Probably most disappointing to seniors was the March 13 message from Banks in which he announced the cancellation of traditional commencement ceremonies. With physical distancing in play, back-to-back gatherings of thousands of graduating students, parents and friends in the Bren Events Center were not in the cards.

“The students had to pivot,” Banks said. “They had to understand this in the context of the larger global issue and think, ‘This is not about UCI trying to oppress me and destroy my life, but UCI is really trying to help me stay alive.’”

“The students had to pivot. They had to understand this in the context of the larger global issue and think, ‘This is not about UCI trying to oppress me and destroy my life, but UCI is really trying to help me stay alive.’”

Kelly Carland, Student Affairs’ director of commencement and special events, was attending a March 10 conference when she learned that it might not be possible to host the ceremonies in their usual in-person format. That gave her three months to pull together an alternative.

“There was no way a virtual commencement would replace walking across the stage and having your name called,” Carland said, “but we knew we had to do something to honor students that was fun and positive.”

Mai Tawfik:

Not able to say goodbye

Mai Tawfik made the most of her four years at UCI. She double majored in political science and international studies. She participated in the UC Washington, D.C. internship program in her sophomore year and studied abroad at The Hague in the Netherlands as a junior. She was looking forward to commencement, at which she would be recognized as an Andrew Carnegie Fellowship nominee and a School of Social Sciences Order of Merit honoree.

But when her mother called on March 10, Tawfik’s campus life was cut short. It was just minutes after the first notice was posted of a potential COVID-19 case at UCI. Although the individual would later prove negative for the virus, Tawfik’s mother wanted her to come home, and she needed to be ready in an hour.

“I was a little panicky,” Tawfik said. “I couldn’t pack everything up in an hour, and I had to work on campus the next day. My roommate thought she had a fever. There were a lot of red flags. I packed as much as I could in an hour and was on my way.”

Home is in Rancho Cucamonga with a tightknit family who immigrated to the U.S. from Egypt in 2011. Instead of her own room in UCI’s Arroyo Vista housing community, Tawfik found herself sharing space with her 27-year-old brother.

There were challenges. With no place for a desk, she studied on her bed or outdoors. It took almost three weeks to get the computer set up so that she could communicate with her on-campus employer. National experts whom Tawfik had lined up to interview for her senior thesis on consensus politics in Egypt became hard to reach in the pandemic. And some instructors, she said, were better than others at remote education.

“I had some anxiety issues,” she said. “Motivation-wise, I was one day up and one day down. Everyone was understanding, but it was frustrating.”

Learning from home, Tawfik missed her support system – friends on the School of Social Sciences Dean’s Ambassadors Council, on which she served, and peers to whom she could vent about daily annoyances.

“One lesson I learned from this is that I don’t take the very small things for granted anymore,” Tawfik said. “My roommate was kind to me all year. I didn’t realize how nice it was to just meet up with someone on campus and have coffee together. It was sad to end my year like that, to not get to say goodbye to the campus.”

The result was a series of online ceremonies that began airing on the commencement website at 10 a.m. on June 13. A campuswide event that included an address by Gillman was followed by smaller school broadcasts and remarks by deans. One highlight was Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, speaking to School of Biological Sciences graduates. Students were encouraged to submit photos of themselves with personalized messages or even 10-second videos.

“We worked with a vendor to do this, and it allowed us to individualize commencement more than we normally would be able to do,” Carland said.

Graduating Anteaters who signed up to participate received a gift box containing a UCI license plate frame, lawn sign, and commencement cap and tassel. Public safety permitting, an in-person ceremony could be held in December 2020 or June 2021 for affected students.

“Our commencement office did a great job of really trying to personalize this,” Banks said, “because it’s a huge milestone in people’s lives, and we wanted to make sure we had the opportunity to celebrate them.”

Dianna Hidalgo:

Making the most of opportunities

Dianna Hidalgo would have liked to walk across the stage as a 2020 graduate in neurobiology & behavior. The first-generation student earned a GPA of nearly 4.0. She won an award for her undergraduate research project on how acetylcholine receptors in the brain affect how we process information. It would have been nice to be recognized for all that, with her family traveling from Alaska to see it.

“It took a long time for me to get here,” Hidalgo said. “I’m 30; I’m older than most students. I didn’t even realize how sad I was about the ceremony until I watched the ‘Some Good News’ show where John Krasinski did a mini graduation ceremony. I cried a little bit. But I’m going for my Ph.D. now, so my family can come for that someday.”

It’s that kind of upbeat attitude that helped Hidalgo take her finals and finish her research project in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. Finals were rough, she said. There was uncertainty about how exams would be administered, and she was concerned about any change in procedure that might affect her high grades. She worried about her job with Alaska Airlines and family members in Peru.

On top of that, Hidalgo had not been able to finish the experiments that would provide data for her Excellence in Research project, which she was conducting through an elite School of Biological Sciences program.

“Luckily, my senior scientist, Irakli Intskirveli, did some of my experiments for me, but then I got all the data at once and had to work 10 to 11 hours a day with the data all by myself,” she said. “But it worked. The project was simple yet insightful.”

Hidalgo did a Zoom presentation for the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program spotlight in June, and her faculty mentor, Raju Metherate, fully expects that it will become the foundation for a first draft of a journal article, on which she’ll be co-author.

Though the finish was rocky, Hidalgo rated her overall experience at UCI a perfect 10.

“When I came to UCI, I was around people who assumed I could do great things,” she said. “I wasn’t used to hearing that. People here believed in me and in each other and in our aspirations.”

And COVID-19?

“Problems always come,” Hidalgo said. “You just have to deal with them and be grateful for what’s going well.”

While the changes have required resilience and flexibility from students, Banks sees that as an advantage in the long run, advancing his goal as vice chancellor to educate “the whole person.”

“I think our students are learning how to lead in unknown times,” he said. “It’s a great lesson for them in how to actually navigate the complexities of life.”