Chapter Three

With the only academic medical center in the nation’s sixth-largest county, UCI Health was uniquely positioned to provide leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic. The mantra rang through the corridors and administrative offices: “We were made for this.”

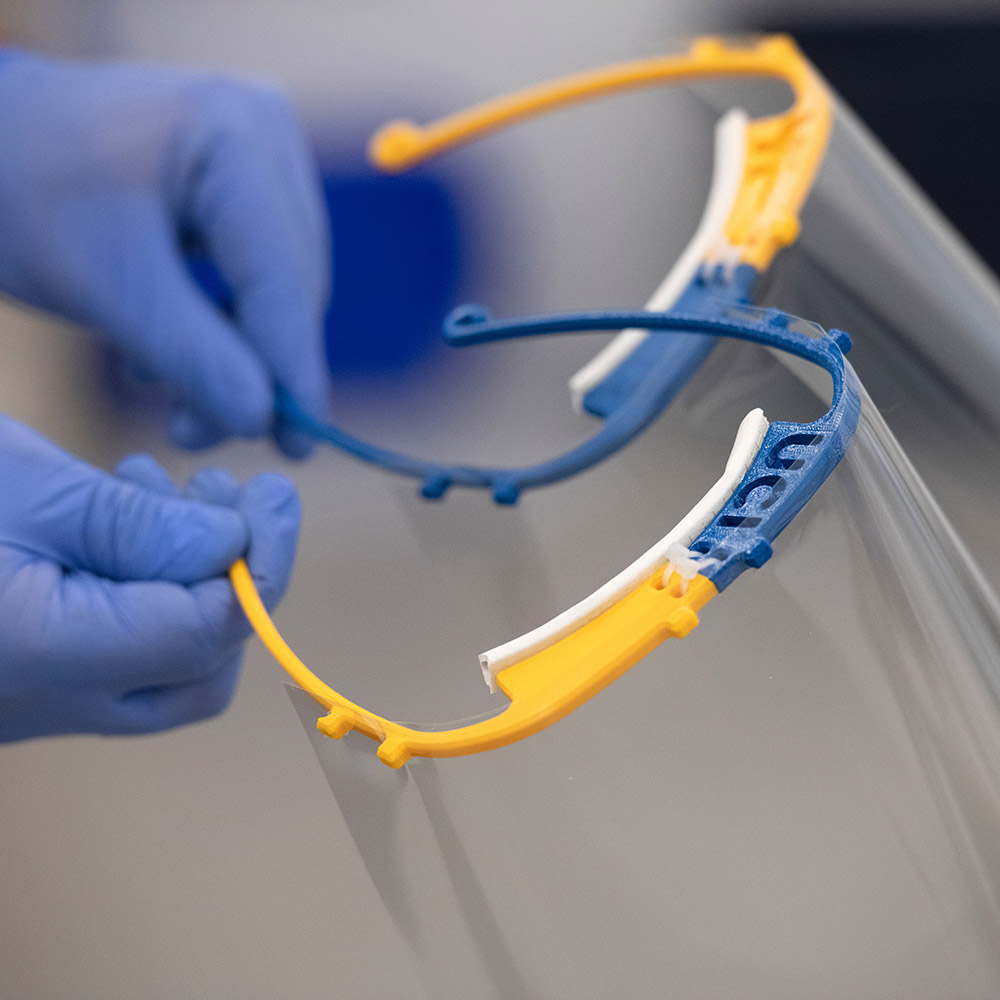

As the clinical hub of UCI Health, UCI Medical Center was ready with infection prevention and pandemic protocols. Staff and doctors had participated in emergency drills. Experts in public health advised and supported the Orange County Health Care Agency, nursing homes and smaller hospitals. And the campus research community jumped in with numerous projects to produce efficient infection and antibody testing, run clinical trials, manufacture face shields and bridge ventilators, and more.

“Very early on, before there was wide recognition, Chancellor Gillman sat down with the cabinet and said, ‘I am concerned. It seems to me that we need to be at the leading edge of designing strategies to keep our students, faculty, staff and community safe if this emerges as a major challenge in America,’” said Dr. Steve Goldstein, vice chancellor for health affairs. “And we were up to the task. UCI has demonstrated the power of an academic health system, bringing the tripartite mission of discovery, teaching and healing to the well-being of Orange County. In a few short weeks, we answered Gillman’s call and were fully up to speed.”

“This was a unique moment for UCI Health and the campus to serve as a purveyor of truth led through science and experts,” added Chad Lefteris, whom Gillman and Goldstein had appointed as CEO of UCI Health in early April. “I’m so proud of my colleagues who are on the front lines every moment of every day doing tremendous work.”

Infection prevention in place

UCI Health’s epidemiology and infection prevention group began tracking what the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was calling a “mysterious pneumonia” coming out of China in December 2019. The EIP team of 15 is led by medical director Dr. Susan Huang, professor of infectious diseases; associate medical director Dr. Shruti Gohil, assistant clinical professor of infectious diseases; and senior director of quality and patient safety Linda Dickey. Its aim is to prevent disease transmission within the medical environment. That includes pandemic planning and evaluation of any global situations that threaten the local community.

The Ebola outbreak in 2014-2016, which never hit Orange County, had provided impetus to look at pandemic infrastructure and supplies. Since then, the EIP group had dealt with measles, norovirus and multiple drug-resistant organisms.

“We had put a sizable amount of effort into a pandemic plan,” Huang said, “actually walking the grounds to find locations for surge, getting multidisciplinary committees together to talk about how we would handle large volumes of infected people, how we might triage and think about conservation of supplies.”

“We had put a sizable amount of effort into a pandemic plan, actually walking the grounds to find locations for surge, getting multidisciplinary committees together to talk about how we would handle large volumes of infected people, how we might triage and think about conservation of supplies.”

Ebola also highlighted the need to ensure the safety of vulnerable hospital personnel.

“We realized very quickly that we had to focus not only on patient safety, but very much on our healthcare workers feeling confident and safe,” Dickey said.

The EIP team watched media reports about the virus in China over the winter holidays. When news of human-to-human transmission came out, members moved quickly, knowing, as Huang said, “that China is only one plane ride away.”

In January, UCI Health set up its hospital incident command center, a network of healthcare leaders charged with facilitating communication, readiness, planning and seamless clinical operations.

“We were way ahead on that,” said Lefteris, who was chief operating officer at that time. “We leveraged our expertise and planning so that we were super prepared.”

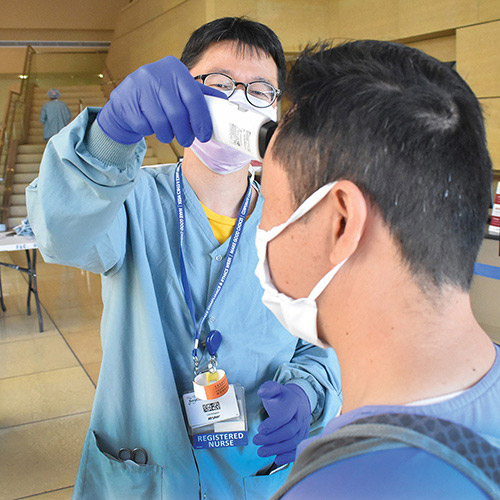

As part of that, the EIP group put its “special precautions” systems in place to deal with a disease that could spread through the respiratory tract. On admission, patients were asked a series of screening questions about travel and symptoms. If their answers pointed to the possibility of COVID-19 infection, the EIP team was notified and those patients were isolated. Medical staff attending them would employ N95 masks, face shields, gowns and gloves. Team members activated these precautions even before they knew what transmission dynamics might look like, Gohil said, and the clear protocol eased healthcare workers’ fears.

“As long as there was a step-by-step program, they knew someone had been thoughtful, and they felt safe because they knew what to do,” she said. “We talked about the fact that we really had two pandemics. There’s the pandemic of COVID-19 and the pandemic of healthcare workers’ fears that absolutely needed to be addressed in order for them to be able to come to work and provide the right care.”

“As long as there was a step-by-step program, they knew someone had been thoughtful, and they felt safe because they knew what to do. We talked about the fact that we really had two pandemics. There’s the pandemic of COVID-19 and the pandemic of healthcare workers’ fears that absolutely needed to be addressed in order for them to be able to come to work and provide the right care.”

Huang said that UCI Medical Center, in an effort to preserve precious N95 masks, was one of the first hospitals in California to begin cleaning and reusing them. The move came in response to the breakdown of supply chains and inability of manufacturers to keep up with increased demand. UCI Medical Center might order 100,000 masks, for example, and receive only 10,000.

“There was a lot of negative press about reuse until everybody wised up and realized we have to plan for a pandemic,” Huang said, “and with communication and understanding, people started to rally around that.”

Once the infection prevention protocols were in place, the EIP team switched to providing consistent, accurate information to the public. A FAQ site on UCI Health’s intranet counted 125,000 hits in two months. Virtual town hall meetings were held. Healthcare providers were constantly reminded that simple procedures – frequent hand-washing, social distancing and staying home if ill – were the best way to stay healthy. Huang and her group relied on science-based advice, trying to counteract alarming but unfounded claims about the coronavirus.

“Our caregivers were running into this fight, and it was scary,” said Lefteris, “especially with so many unknowns, so we took it upon ourselves to try to limit the anxiety by providing factual information as much as possible.”

“Our caregivers were running into this fight, and it was scary, especially with so many unknowns, so we took it upon ourselves to try to limit the anxiety by providing factual information as much as possible.”

In all, 92 healthcare providers, or just under 1 percent, had tested positive for COVID-19 by early June, and 83 percent had recovered and returned to work. At that point, Lefteris said, none of the cases had resulted from a protective equipment breach on the job. Instead, they had been community-acquired.

Very early, UCI Health launched an organizationwide effort to support employees in many different ways. This included an on-site commissary where medical staff could get free groceries, no-cost child care options, and a well-being initiative at the Susan Samueli Integrative Health Institute to provide complimentary online courses to alleviate anxiety and stress.

Treating patients

The first COVID-19 patient came to the medical center on March 12. With some of a $2.5 million gift from the John and Mary Tu Foundation, the hospital had purchased tents and erected them outside a week earlier. That’s where people were screened and tested before entering the facility. If necessary, the tents could have housed beds for a surge. However, Goldstein said, “we managed to modify hospital operations quickly enough that the tents were used only for safe evaluation and intake sites.”

When UCI Health staff began reaching out to non-COVID-19 patients to offer safe alternatives to in-person clinic visits, the health system’s telemedicine enterprise boomed. At their peak, virtual visits accounted for about 50 percent of outpatient care in one month’s time, and the service has received rave reviews from patients and providers.

Enhancements to telemedicine had originally been scheduled for August 2020, said Tom Andriola, vice chancellor for information, technology and data, but in light of the pandemic, his team pulled new capabilities together by April 1.

“We had a huge lift from our information technology staff,” Lefteris said. “It wasn’t a simple thing to make sure medical records were perfectly documented in the electronic data and everything was HIPAA-compliant [to maintain privacy], but the team rapidly solved the issues.”

He expects to see more post-pandemic growth in telemedicine, with the potential for big changes to healthcare delivery in the long term, based on experiences during this pandemic.

Another innovation was UCI Medical Center’s ability to ramp up in-house COVID-19 testing beginning March 19. Early on, the only test option had been through the already inundated Orange County Health Care Agency, which could take up to 12 days to return results. Dr. Edwin Monuki, head of pathology and laboratory services at UCI Health, and hospital leaders reached out to medical companies they had long-standing relationships with and were able to find a reliable test. With the Tu Foundation gift in hand, the medical center quickly purchased a needed piece of equipment, and UCI’s own lab technicians were then able to conduct 1,000 COVID-19 tests per day with same-day results.

UCI was the first hospital in Orange County to do in-house testing, Monuki said, and the project was completed more than two weeks ahead of schedule. He is now regularly asked to confer with doctors around the world on testing protocols.

Drive-thru testing, the brainchild of Dr. Michael Stamos, dean of the School of Medicine, solved the issue of how to safely swab large numbers of people without bringing them into the hospital. With nurses staffing the testing stations, Goldstein said, the sites became a model for providers across Orange County.

As part of preparation for a potential COVID-19 surge, Lefteris also worked with surgical services leaders to forge a plan to defer non-urgent surgeries and procedures. The move helped UCI Health manage its supply of personal protective equipment. By early June, surgical volume had resumed at 100 percent of the pre-March level, significantly helping the health system recoup financial losses experienced during the stay-at-home period.

Providing community assistance

Drawing on its deep expertise in medicine and public health, UCI was able to offer valuable assistance to the local community throughout the spring. Joe Brothman, director of environmental health and safety at UCI Health, convened incident commanders from other Orange County hospitals and the Orange County Health Care Agency every Friday to share findings, advice and best practices.

Bernadette Boden-Albala, director of the Program in Public Health and founding dean of the proposed School of Population Health, who had established a good relationship with OCHCA, was tapped early to provide pandemic models for the agency forecasting the health and economic impacts of COVID-19 and assessing the different effects within ethnic groups and the probabilities of a disease surge.

She relied on modelers from public health, computer science, mathematics and the hospital for the job. In those early weeks in March, the number of COVID-19 cases was doubling every three days. Models showed a surge occurring the second week in April if the trend continued. Those forecasts were a huge impetus, along with action from the state, for Orange County’s shelter-in-place order.

“Luckily, we did not have that surge because our actions flattened the curve,” Boden-Albala said, “but we were talking with OCHCA every day about the changing numbers and what they meant.”

And UCI has continued partnering with OCHCA, particularly in surveillance. Boden-Albala is currently leading a random sampling of 5,000 people across the county to identify – via a microarray platform developed by UCI scientists – those with COVID-19 antibodies in an effort to determine how many have been exposed to the coronavirus.

UCI’s public health and medical staff also collaborated with major Orange County businesses on back-to-work plans and helped first responders, nursing homes and smaller hospitals with testing.

Putting research into action

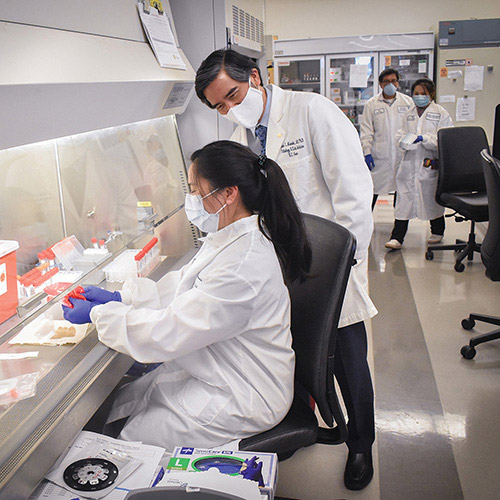

The “discovery” aspect of UCI Health’s “discover, teach, heal” mission positioned its physicians to lead key research on the disease.

Stamos worked with the UCI Office of Research to acquire $1.25 million from campus sources and combined it with another $1.25 million from the Tu Foundation gift to swiftly create the COVID-19 Joint Research Fund.

Dr. Dan Cooper, pediatrician and director of the Institute for Clinical and Translational Science, was instrumental in efforts across all five UC medical centers to drive clinical research on convalescent serum from people who have recovered from COVID-19.

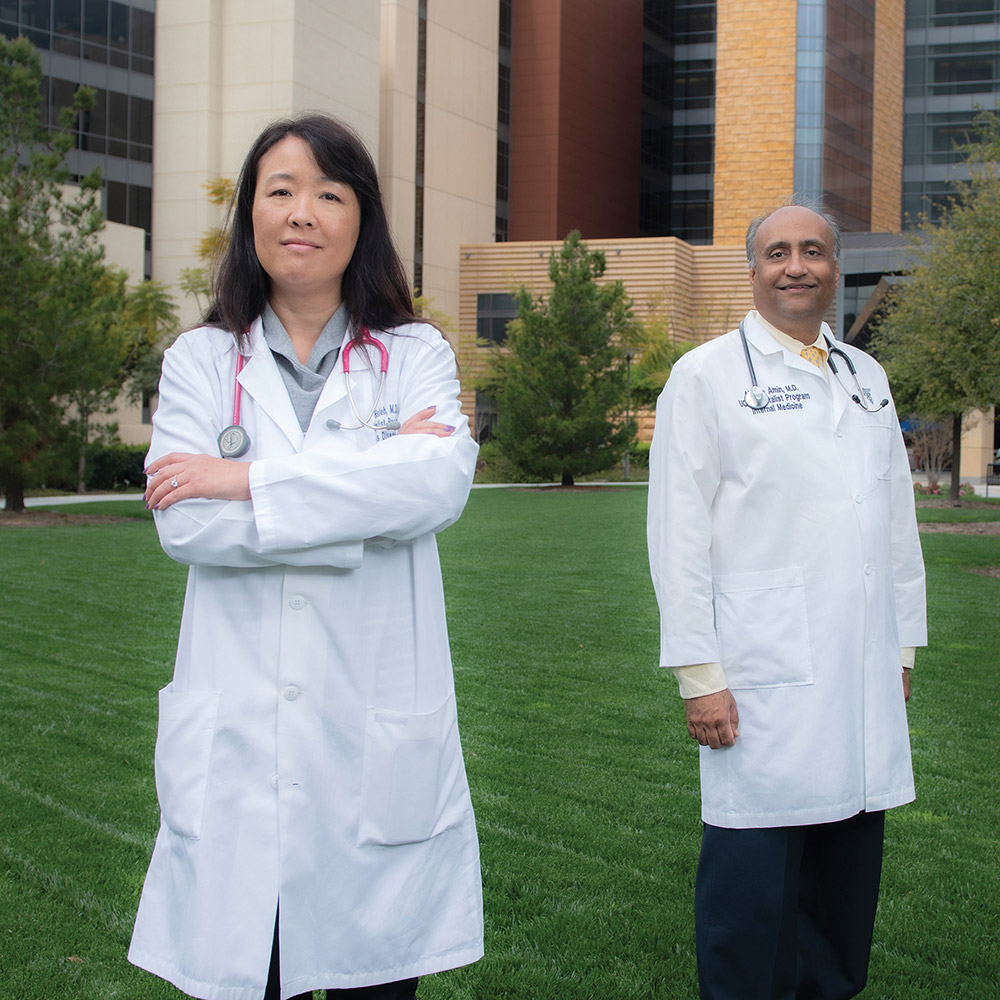

In March, Drs. Alpesh Amin and Lanny Hsieh launched the UCI branch of a clinical trial that spanned the nation to test the efficacy of the antiviral drug remdesivir as a potential treatment for the disease. It’s now approved for clinical use.

“Our vaccine and therapeutics development groups rapidly focused their attention on SARS-COVID-19 with grants from the Joint Research Fund,” Goldstein said, “and federal support from the Department of Defense and the National Institutes of Health.”

At the same time, Andriola’s group developed a database program that collects COVID-19 patient information from all UC campuses to enable efficient evaluation of treatments and clinical trends.

“I could not be more impressed by how our students, faculty, staff and leaders have proven themselves. To a person, they have exemplified what can be achieved when you are thoughtful, creative, generous and collaborative in the service of the community and in support of the state and country,” Goldstein said. “There is no part of UCI that I am not proud to brag about.”