“My family is very matriarchal. I have always admired my mother and grandmother, who taught me how to navigate the complexities of being a woman in a patriarchal world. In addition, I deeply admire Supreme Court Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor. She was a first-generation law student from a working-class family, much like my own. Although she holds the highest possible position in the U.S. legal system, she remains tough and proud of her roots. She embodies the kind of professional woman I would like to be.”

When President Donald Trump announced last September that he planned to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, Viridiana Chabolla Mendoza, a DACA recipient and first-year UCI law student, felt the same way as thousands of other so-called “Dreamers”: anxious, scared, stressed, uncertain. But just two weeks later, when she became a plaintiff in a lawsuit against the president of the United States, another emotion joined the mix: determination.

Chabolla was born in Mexico but raised in East Los Angeles, which she has called home since she was 2. Because her favorite childhood hobbies were reading and writing, her grandparents suggested that she become a lawyer. Her undocumented status, though, made it difficult for her to attend college (she went to Pomona College) or find employment.

First introduced in 2001, the DREAM Act – Development, Relief & Education for Alien Minors – proposed a route to legal residency for individuals like Chabolla but was never approved by Congress. The DACA program, however, established in 2012 by the Obama administration, afforded many of the same protections to undocumented people brought to the U.S. as children. This eased Chabolla’s path to UCI’s law school, which she began last August.

Just weeks into her first year, after President Trump’s announcement, she was approached by Mark Rosenbaum, an attorney for the pro bono law firm Public Counsel and adjunct professor of law at UCI. He had a case pending against the U.S. on behalf of DACA recipients who had identified themselves to the government in exchange for legal permission to live and work in America. The current president’s intent to rescind this deal could constitute a violation of the Fifth Amendment’s equal protection component.

Rosenbaum had a question for Chabolla: Would she be a plaintiff?

Having worked as a Public Counsel organizer, she was used to recruiting plaintiffs for cases. Now, for the first time, she was “on the other side – and it was daunting.”

Hesitant to accept, Chabolla remembered how Rosenbaum had always been interested in her well-being as a DACA student, checking in on her often during her transition to law school. And knowing the other lawyers on the case – “an incredibly compassionate and dedicated group” – helped ease her mind. After conferring with family and friends, Chabolla became one of six plaintiffs in Garcia v. United States of America, filed Sept. 18 in the Northern District of California.

“I’m generally a private person, so the national attention was a little uncomfortable at first,” she says. “Not to mention that at the same time the case was beginning, I was adjusting to law school, which is wildly fast-paced as it is. Luckily, I have a wonderful support system, so that’s made it easier to juggle everything.”

Chabolla, who aspires to a career in litigation, knows how long the hearing process can take. It could be several months, and possibly years, before Garcia v. U.S.A. reaches the Supreme Court. Nevertheless, she’s glad to be part of a case “that furthers court delays of DACA’s end, so lawmakers are under less pressure to pass just anything and can take more time to lobby for a ‘clean’ DREAM Act,” one that doesn’t include funding for a border wall or detention centers.

Most of Chabolla’s work as a plaintiff involves sharing her story with lawyers and clearing up the public’s misconceptions about the DACA program, which she says gives her purpose as she both pursues her law degree and represents “Dreamers” nationwide in court.

“I hope that at the end of all this there are some legal protections in place for me, so I can continue practicing law, and for thousands of other immigrant youth whose futures are up in the air right now,” Chabolla says. “Working toward that end makes everything worth it.”

- Megan Cole

“Serving in bulk is so environmentally beneficial, and in a way, it creates a community. You go over to the vat at Costco to put relish on your hot dog, and you’ve got a chance to say hello to someone,” she says, chuckling. “But when all you’ve got is the end of your little package to tear off, you know no one’s coming over to chat with you.”

“Serving in bulk is so environmentally beneficial, and in a way, it creates a community. You go over to the vat at Costco to put relish on your hot dog, and you’ve got a chance to say hello to someone,” she says, chuckling. “But when all you’ve got is the end of your little package to tear off, you know no one’s coming over to chat with you.”

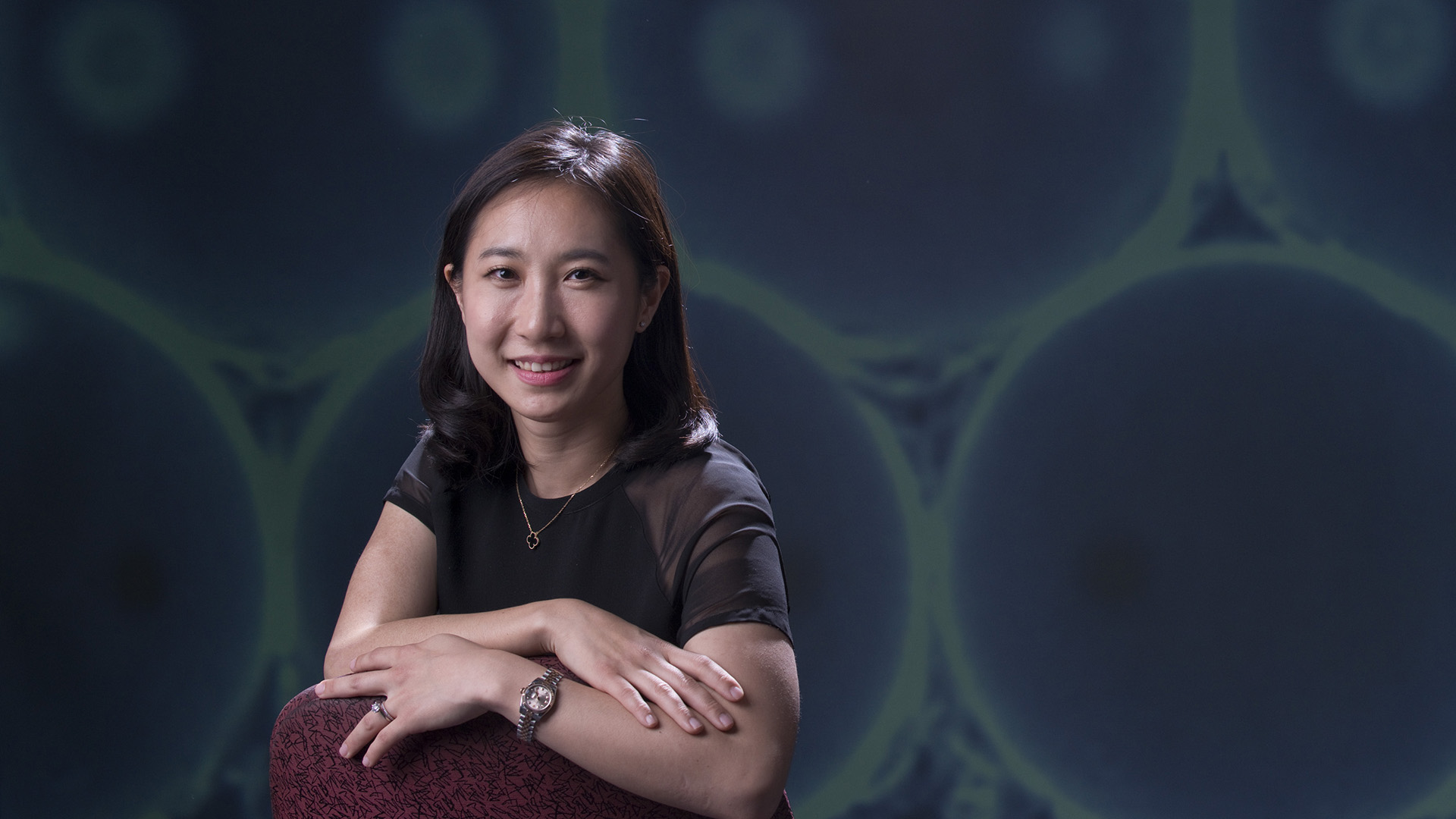

Q: You’ve been touted as one of the “top five women in gamification.” How does it feel to be a role model to a new generation of female game designers?

Q: You’ve been touted as one of the “top five women in gamification.” How does it feel to be a role model to a new generation of female game designers?

Natoolo was born in rural Uganda, the youngest of 28 siblings. Her Rwandan mother witnessed the beginnings of genocide in her homeland and escaped in the 1950s to Uganda, where she started a family. Natoolo’s father, a lawyer trained at Oxford University, instilled a fierce love of education in his children; he saw it as “the only way out of poverty.” Natoolo’s family, whom she calls “the village that supports me,” often went without electricity, food or any means of transportation, but this never stopped Natoolo from walking two hours to school.

Natoolo was born in rural Uganda, the youngest of 28 siblings. Her Rwandan mother witnessed the beginnings of genocide in her homeland and escaped in the 1950s to Uganda, where she started a family. Natoolo’s father, a lawyer trained at Oxford University, instilled a fierce love of education in his children; he saw it as “the only way out of poverty.” Natoolo’s family, whom she calls “the village that supports me,” often went without electricity, food or any means of transportation, but this never stopped Natoolo from walking two hours to school.