Carbon, nitrogen and plastics

When you clean your polyester tracksuit, yoga pants or polar fleece pullover in a washing machine, the water that drains out and eventually reaches the ocean contains microscopic, rod-shaped synthetic fibers. Zooplankton, tiny aquatic animals, can sometimes mistake these multicolored bits for their natural food.

“It’s the same as when mercury or DDT goes into the food web at the lower levels and bioaccumulates as it gets eaten by animals higher up the chain,” says Kate Mackey, UCI’s Clare Boothe Luce Associate Professor of Earth System Science. “These guys should be eating phytoplankton, but if you have a plastic particle that’s the same size and shape and color as a phytoplankton cell, these little animals can’t necessarily distinguish.”

Jessica Walden, a Ph.D. candidate in Earth system science, has made marine plastic pollution her main research target. Working at field sites in Torrey Pines and Los Penasquitos Lagoon in San Diego County and spending countless hours in Mackey’s laboratory in Croul Hall, she’s trying to determine what influences the ingestion of microplastics by zooplankton.

“We use plastic beads that can be made in various shapes, sizes and colors, and we can also use some that are fluorescent,” Walden says. “We add them to a culture with zooplankton – including Artemia salina, a kind of brine shrimp – to see if they prefer plastic over phytoplankton or vice versa or if they’re just grazing indiscriminately.”

After the zooplankton steep for some time in a petri dish, the scientists dissolve the animals’ shells and meticulously count the number of plastic particles they’ve ingested. “We see their guts full of plastic,” Walden says. “We have evidence they’re eating microplastics that humans are introducing into their habitat.”

The problem this creates, according to Mackey, is that a portion of what the sea creatures are consuming is filling but has no nutritional value, causing the animals to slowly starve. And when zooplankton eat plastic, the larger fish and other sea creatures that eat zooplankton are also dining on the useless filler.

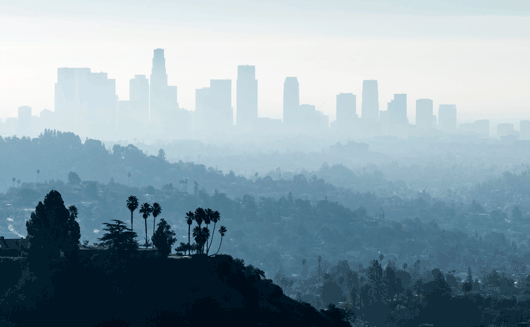

Another graduate student in the Mackey lab, Christopher McGuire, a Ph.D. candidate in Earth system science, also spends time in lagoons along the Southern California coast. He’s looking into phytoplankton community composition, different species, nutrient inputs in the environment and nutrification – via excess fertilizers running off the land into the watershed.

“Everyday neighborhood activities, such as the application of fertilizers or pesticides to your lawn, can directly impact water quality along the coast,” McGuire says. “In Los Penasquitos Lagoon, we’re trying to evaluate how changes in phytoplankton populations are impacting larger species – baitfish such as smelt and even California halibut, for example – who use these relatively protected inland waterways to rear their young. I hope this work will ultimately influence policymakers to adopt guidelines to curtail the use of potentially harmful household chemicals.”

“Everyday neighborhood activities, such as the application of fertilizers or pesticides to your lawn, can directly impact water quality along the coast.”- Christopher McGuire, a Ph.D. candidate in Earth system science

Off the coast of Newport Beach, UCI researchers in the lab of Adam Martiny have witnessed shifts in plankton communities due to ocean heating over the past decade. Martiny says these differences are impossible to directly attribute to human activities.

“But having experienced a very large El Nino, resulting in significant warming, we can say that such El Nino events in many ways provide a ‘preview’ of future climate change effects,” says Martiny, professor of Earth system science and ecology and evolutionary biology. “Warming has led to a shifting ocean chemistry, smaller phytoplankton and less algae biomass. This may be a good or bad thing as algae help take up CO2 and provide food to animals – but they can also produce harmful toxins.”

Farther out to sea, UCI Earth system science Ph.D. student Ashton Bandy is working with the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project on a sweeping investigation into ocean acidification. She and other researchers collect samples from the Southern California bight, a curved section of coastline that runs from Santa Barbara County down to Baja California in Mexico and is a highly productive marine habitat. They’re studying the environmental DNA of the species they find to determine which are present at a given time.

“SCCWRP wants to know how ocean acidification, which is caused by an overabundance of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, is affecting different calcifying organisms, such as crabs and oysters – anything that uses carbonate to make a shell,” Bandy says. “We want to use satellite data to look for frontal systems where two bodies of water come together to create chemical gradients and explore how that can introduce nutrients that influence the way phytoplankton grow.”

As in other aquatic settings, phytoplankton feed zooplankton, fostering a habitat where fish like to breed and grow. The ultimate goal of the SCCWRP project is to see how these region-spanning processes can impact fisheries and economies that support many people.

“The idea is that we can model this system that scales up from fundamental nutrients all the way to global commerce here in Southern California,” Mackey says, “and that framework can be applied in other similar settings around the world.”

– Brian Bell, UCI